I have recently completed a 24-hour period in which I had the distinct displeasure of shooting with the biggest hunk-o-junk in the history of hunk-o-junkdom.

The hunk in question is the Soviet-era Russian Agat 18K — a half-frame toy camera that, if given to an actual child, would undoubtedly necessitate in a lifetime of psychotherapy.

Like most fiascos, my time with the Agat 18K began with good intentions. Creatively intoxicated by my glorious experience with the Ricoh Auto-Half, the seeds of a new idea began to germinate in the old encephalon. “Why not,” I thought, “build myself a legacy as a ‘half-frame photographer?’” As niches go, it’s reasonably untapped, and I thoroughly enjoy both the half-frame shooting process and its results. Besides, it would be a step up from my current legacy as an ‘irrelevant photographer.’

My first order of business, prior to purchasing any new film camera, is to assuage my guilt over already owning far too many. Deftly deploying the acrobatically inclined synaptic leaps of a world-class rationalizer, I invented a theory that half-frame cameras should only count as half-a-camera in my inventory total. Dodgy justification in place, I guiltlessly began researching which half-frame camera would next aid my newly-anointed legacy.

This time around, I wanted a camera that offered a bit more control than the point-and-shoot models I’d been favouring, yet remained ludicrously inexpensive. This short but simple set of requirements led me straight to the Agat 18K.

Gleaming with the sumptuous glow of my monitor’s LED backlight, the Agat appeared to check all the right boxes. It sported both manual focus and manual exposure. It was cute, which seems to be a design aesthetic shared by all the best half-frame cameras. The internet was chock-a-block with rave Agat 18K reviews, and it even possessed that one special feature I look for in every new film camera — something I call the “discombobulation factor.” The Agat’s d-factor comes courtesy of its vertical orientation, which (if held as designed) results in landscape-oriented photos rather than the portrait aspect of most half-frame cameras. But the most important factor was its price: $25. Canadian. Plus another $6 to ship it from Belarus.

I could see no possible scenario in which the Agat 18K wouldn’t yield at least $31 worth of fun — even if it completely and totally sucked.

I was wrong.

The camera found its way from Belarus to Vancouver far quicker than expected. I’ve placed expedited Fed Ex deliveries within Canada that took longer to arrive. Combining hindsight with cynicism, I suspect the seller was highly motivated to unload it as quickly as possible — lest I change my mind. I extracted the tiny camera from the center of a 10 meter spool of bubble wrap, and examined it carefully. Cosmetically, it looked about as fine as a 31 year old plastic toy camera can look.

Glancing at Vancouver’s weather forecast and seeing a queue of unseasonably warm and sunny days ahead, I grabbed a roll of expired Kentmere 100 from the back of the freezer, and began to load the camera.

Here’s where the story darkens.

My first attempts to advance the film proved futile — the advance knob would turn, but the film would not wind. Consulting the owner’s manual, I was faced with the realization that I couldn’t read Russian. So I turned to the internet instead, where I learned that the Agat’s advance knob has a little button in the middle. When it points to a red dot, the button pops up and the camera is in rewind mode. When it points to the white dot, the film can advance. My button was clearly pointing at the red dot, but it was not raised. I tried to spin the button around to the white dot — it wouldn’t budge. I tried to gently coerce the button into popping up. It remained firmly seated.

This was the first of several hundred times that I would attempt to fix an issue by slamming the camera against a hard surface — and unlike many of the subsequent slams, this one worked. The button popped up.

Alas, that had no effect on the camera’s function, since the film still wouldn’t advance unless the button pointed toward the white dot. Noticing that the button was knurled, I pulled out a screwdriver, nestled the blade up against one of the knurled ridges and, with brute force, slowly worked the button around to the white dot.

Thus positioned, I turned the advance knob, only to watch it spin freely around the inner button causing it to point, once again, to the red dot. I repeated the brute force and screwdriver method several more times until, eventually, I could advance the film by pressing my thumb hard against the inner button while slowly and carefully rotating the knob — a technique that required about 15 seconds of fiddling between photos. Since this is a half-frame camera, that meant at least 72 fiddles per roll, which was not a viable long term solution. So I decided, upon completing this test roll, that I would super-glue the rewind button to the advance knob, allowing me to effortlessly advance the film — even though it meant I’d forever need to open the camera in a changing bag.

Exposure is set via pictograph, thus ensuring that the camera’s intended market — children in the 1980’s — would never learn the basic practice of manual exposure setting. Which worked out perfectly, given the eventual domination of smart phone cameras.

The pictographs control both the aperture and shutter speed. When the aperture gets wider, the shutter gets slower. A little table in that Russian language manual spells out the relationship precisely. What’s humorous is the documented specificity of these values: At f/2.8, the shutter speed is listed as 1/130; at f/4 it’s 1/169; at f/8 it’s 1/262. Personally, I find it rather difficult to accept that a plastic toy camera that’s unable to make a pop-up button pop-up is capable of microsecond shutter accuracy. But the Agat’s optimism did provide me with at least $1 or $2 worth of entertainment, so I was well on my way toward recouping my $31.

The Agat’s manual focussing feature is a bit more traditionally “manual” than its exposure setting, though not without issues. Focus is set by rotating a small ring around the front of the lens. The ring turns effortlessly — too effortlessly. So loose is this ring, that a gentle breeze is all the force required to rotate it out of position and, thus, out of focus — the sort of gentle breeze that can be generated by as benign an action as simply walking with the camera.

Furthermore, the camera’s discombobulation factor — its vertical design orientation — proved more discombobulating that I’d imagined. Operating it as designed requires jutting your elbows all akimbo, whilst attempting to pinch the top and bottom of the long-edge of the camera with one hand while your other hand is asked to plunge a button — located on the front face of the camera — directly toward your face. After a bit of experimenting, I discovered that holding the camera upside down felt slightly more ergonomic, though it was then impossible to read the exposure values or check the latest status of the focus ring.

Still, with all these quirks, I was encouraged, engaged, and excited to begin shooting. And for two or three shots (save for the hassle of advancing the film), I was almost happy.

On the fourth shot, I pressed the shutter button and nothing happened — a seemingly innocuous event that marks the precise moment at which I began my descent into madness.

My experience with the Agat 18K’s shutter release and transport mechanism has revealed an inadequacy in the English language. Specifically, there is no word in the dictionary that means “really, insanely, super frustratingly, annoyingly flawed.” So I’m taking the opportunity to coin the term risfaf. Feel free to add it to your daily lexicon.

That first shutter failure was, in and of itself, not overly alarming. These things sometimes happen with old film cameras, and are somewhat expected on those with dubious lineage. So I simply tried pressing the shutter again… and again… and again. Sensing a pattern, I altered my pressing technique. I came at the button from the top, the bottom, the left, and then the right. Click! On the eighth press, with the button pressed at a 45 degree angle, I finally took a photo. I jammed my thumb against the knurled button on the bottom of the camera, gingerly advanced to the next frame, awkwardly placed the camera to my eye and pressed the shutter button. Once again, the camera failed to take a shot.

Convinced I’d learned the secret method with the previous frame, I immediately tried releasing the shutter using the same 45 degree press from the right. Nothing. I tried again. Nothing. After 10 or more presses from various angles, the shutter released.

With each frame came greater agitation. Twenty, and sometimes thirty presses were required to release the shutter. Sometimes it would release with a flick of the finger to the side of the button. Sometimes it would release if I rotated the button while plunging it. Only two things were certain: first, it would never release on the first several tries; and second, it would never release the same way twice.

By around the tenth shot, I was painfully aware of the sideways glances I was getting on Vancouver’s seawall. Apparently, it’s considered a form of aberrant behaviour to stand in one spot for 4 or 5 minutes, while repeatedly pushing a button on a black and yellow plastic toy camera.

My behaviour grew demonstrably more aberrant once I’d finally exhausted every possible way to push the button, and began whacking the camera against the palm of my hand. This worked for a little while, until such time that it needed firmer contact with my fist and then, eventually, the side of a building or a steel railing.

Equally annoying was that, when I did manage to finally release the shutter, the film advance knob would often freeze, requiring spectacularly barbaric whacks against the cement sidewalk before it would again allow the film to advance.

After spending nearly two hours to take a mere 20 photos of absolutely nothing worthwhile, I was overcome by a powerful desire to throw the camera in the trash. But I am neither a rash nor emotional person so, instead, I brought the camera back to the condo, sat it on the kitchen counter, and decided I’d deal with the issue the following day. Besides, after seeing how badly this camera handles, it would be a real shame if I didn’t also get to see whether its image quality was equally atrocious. I had to find a way to finish that roll.

The next day, possessed with renewed (though thoroughly unjustified) optimism, I stared at the little Agat all throughout breakfast. I knew it would haunt me until I picked it up again, so I thrust a jeweller’s loupe in my eye socket, and began to carefully inspect the camera for a solution. And sure enough, I found one!

It turns out that cheap little yellow plastic shutter release button is threaded! A whole new way to try to release the shutter! I dug through a drawer, pulled out an old school remote mechanical shutter release, and screwed it into the button. I plunged the trigger on the shutter release, and the cheesy little Agat made a decisively positive click. I shoved the camera and the remote shutter release into my pocket and took off for Canada Place.

I spent several wonderful seconds aligning pictographs, framing shots, and shielding the persnickety focus ring from the gentle, spring-like breeze — holding the camera in one hand while releasing the shutter with the cable release clutched in the other.

Buoyed by the belief that the Agat 18k had not beaten me, I proceeded to run off a string of two straight shots until, on the 3rd, the film jammed. Fortunately, one whack on the rail and all was well for another two shots — until the shutter again failed to fire. After dozens of tries with the mechanical release, I unscrewed it, and returned to the previous day’s technique of pushing the button from every possible angle, until I again resorted to smacking it against a rail for several minutes until it finally released.

Once more I pressed my thumb against the rewind button and began to slowly rotate the advance knob — until it seized up half-way to the next frame.

At this point, no amount of pushing, plunging, whacking or smashing would free the camera. It was well-and-truly frozen. I shoved the camera into my pocket and headed home.

Back in the condo, using an assortment of hammers, screwdrivers and pliers, I managed to free the transport and advance the film one more time — at which point it froze again.

With over a half-roll of film remaining, I’d had enough. I plunged the camera into the dark bag, extracted the film into my stainless tank, and dunked it in some Rodinal. It was time to see the fruits of my labours.

As bad as the camera functions, I was actually rather surprised by the image quality. It wasn’t half-bad.

Of course, “half-bad” didn’t include the numerous frames that exhibited visible light leaks, nor those in which the light leaks threatened to take over the image, nor even those times when the light leak was so egregious that it obscured the entire frame. Nor does it include all those times when the focus ring spun itself out of focus, nor those other frames when I accidentally took a selfie because the shutter released while I was smacking the camera against a firm surface…

OK. So I rarely managed to get an issue-free shot with the Agat 18K. But when it happened, it was surprisingly good — providing you don’t mind excessive barrel distortion, really soft corners, or… oh, never mind.

Granted, there’s a certain serendipitous charm to the images. But since a similar effect could easily be achieved by closing my eyes and twirling around in a circle until dizzy, I’m not sure it’s worth the frustration.

Needless to say, this is not a camera you’ll turn to when your photos require split second timing. Nor is it a camera you’ll turn to should it be absolutely essential that you take a photo some time that day. And it’s most certainly not a camera you’ll choose to use if, like me, you believe every moment of life is precious. Which is why it’s highly unlikely I will ever spool another roll of film into this thing.

What’s truly surprising is that this model — the Agat 18K — is an improved version of the older, earlier Agat 18. Since the “K” obviously stands for “Krap,” I can’t even imagine what the K-less model would have been like.

Granted, this is a 31 year old Soviet-era plastic toy camera… so one’s expectations must be sufficiently subterranean. And I’ll readily admit, given the plethora of rave reviews this camera gets on the internet, my particular model may have some accelerated degradation issues. I would be fine if the Agat’s shutter were to release oh, say, every second or third time I pressed it. And if it only locked up once or twice a roll, I’d be able to live with that. It would definitely be nice if the frame advance actually advanced the film and, when it did, wouldn’t shred the sprocket holes. I could even live with the light leaks and the free spinning focus dial. But this camera is a long way from being that camera. Quite simply, this camera is risfaf.

©2019 grEGORy simpson

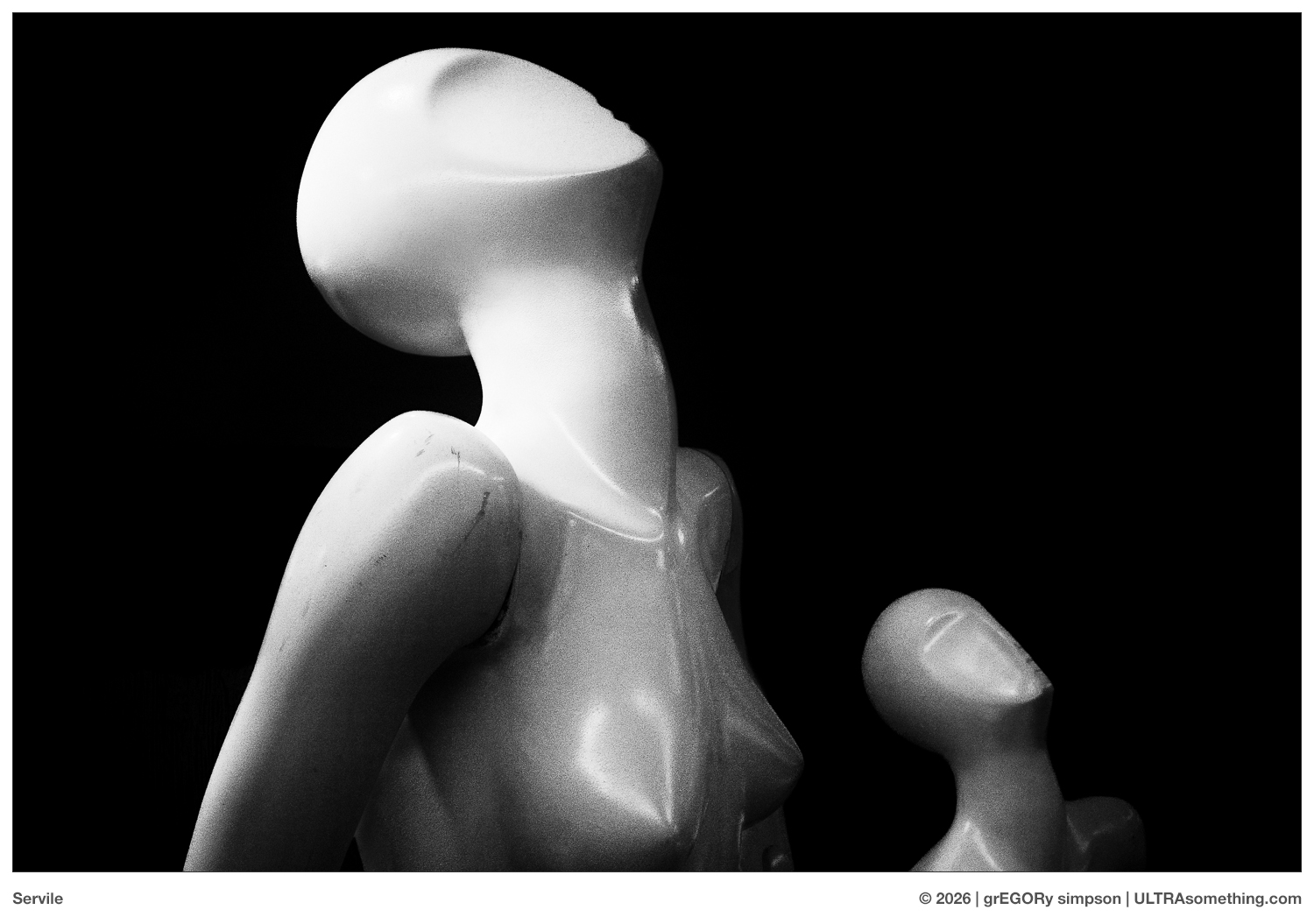

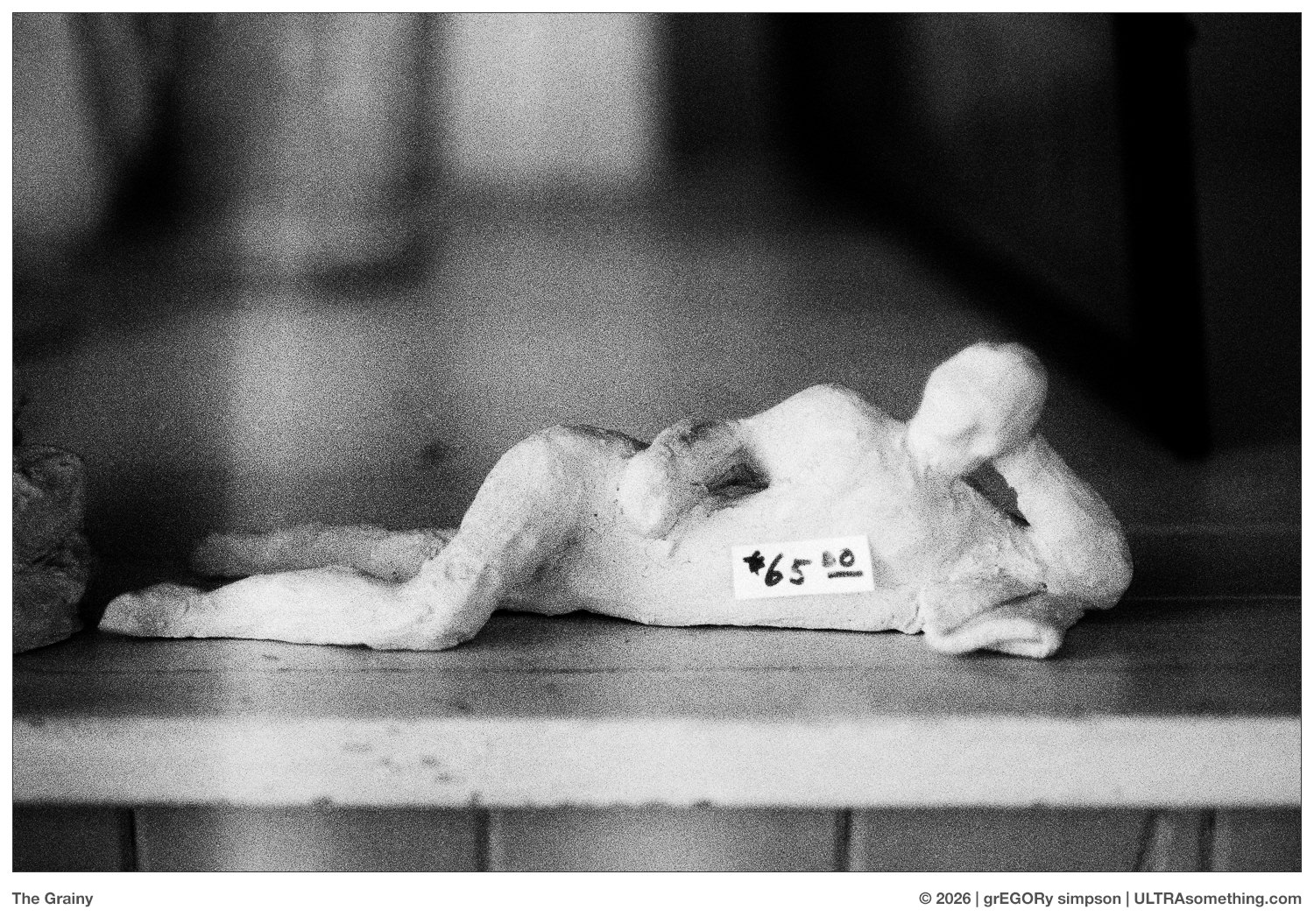

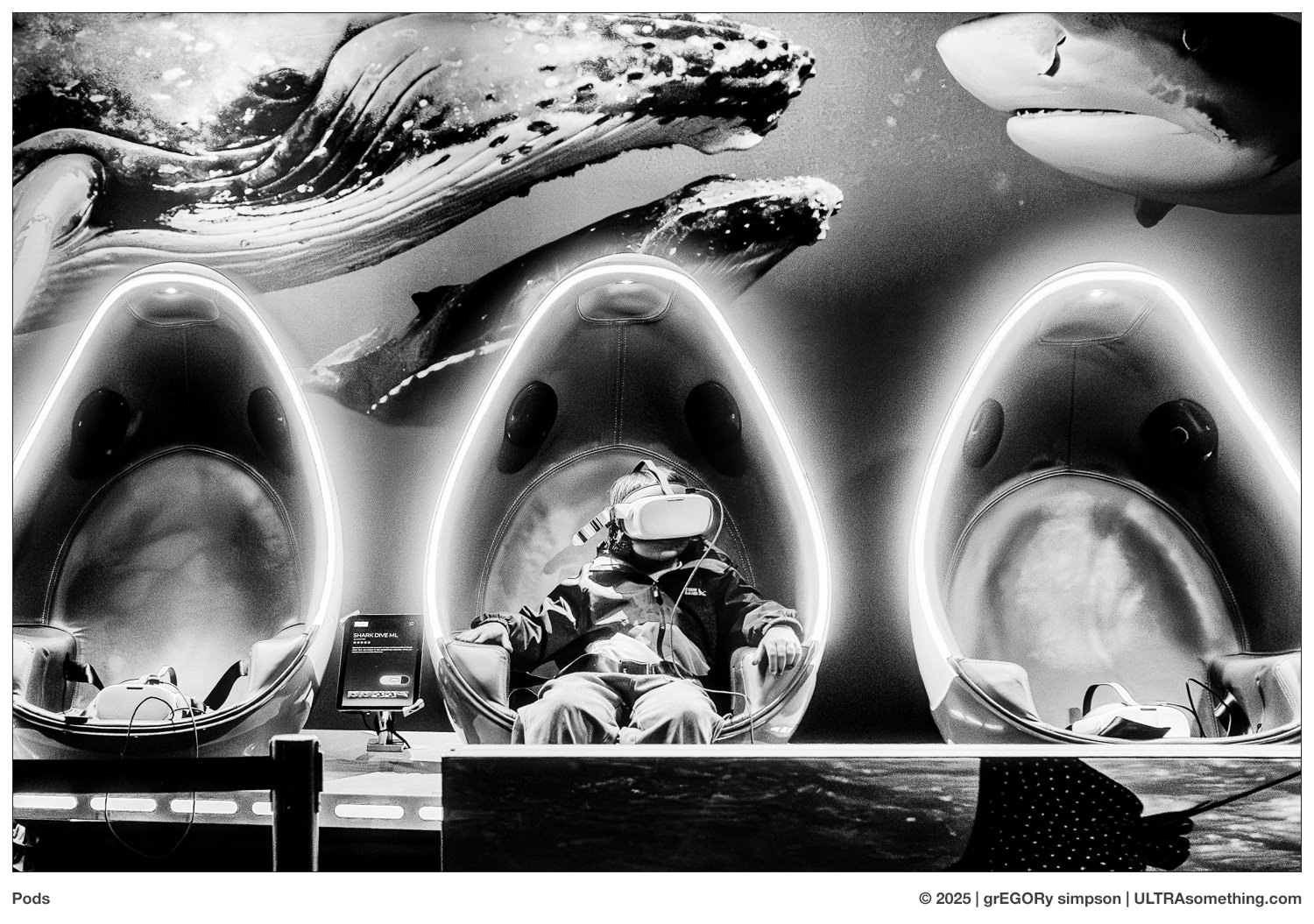

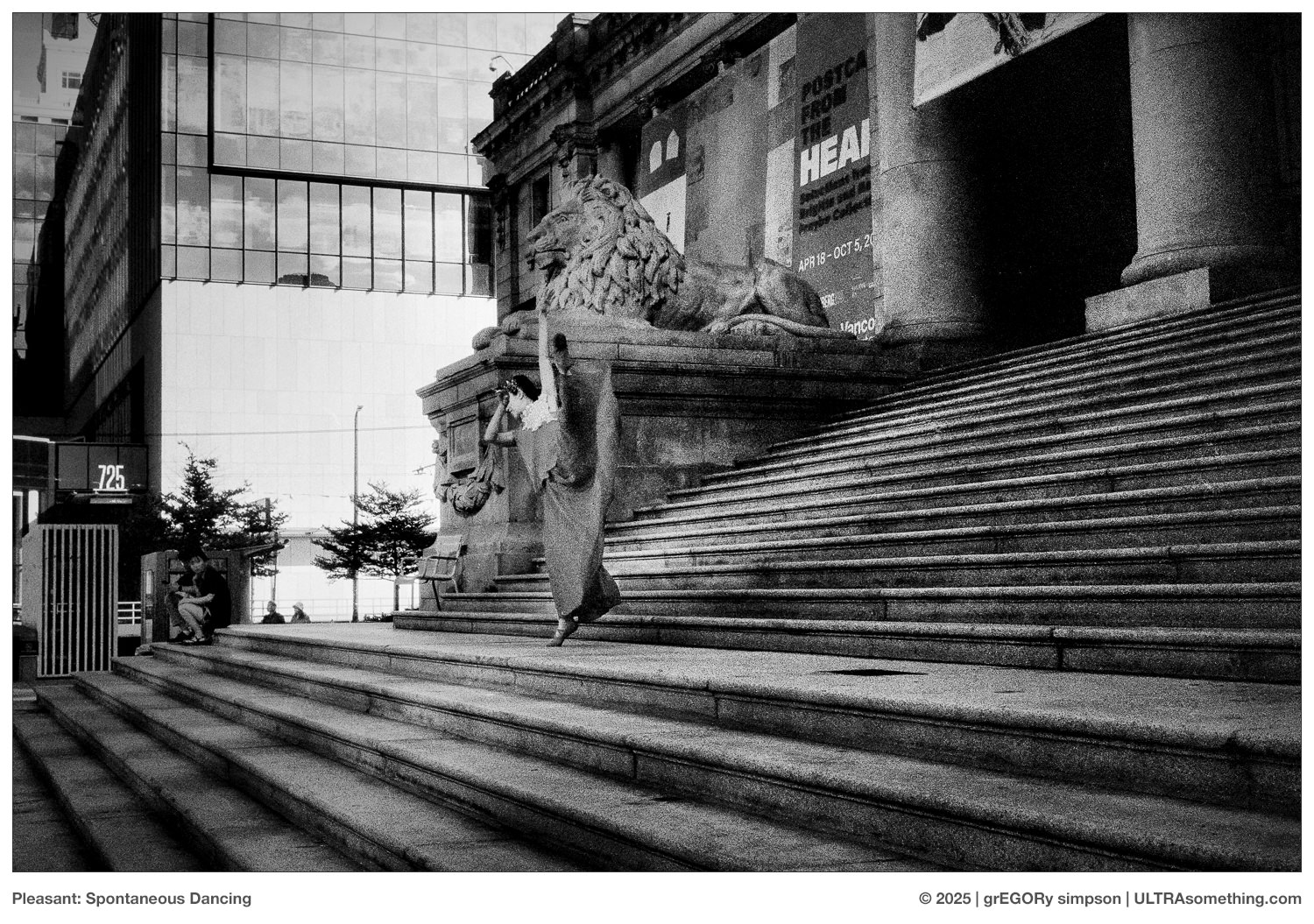

ABOUT THE PHOTOS:

All photos (except for the camera itself) came from the 1/2 roll of Kentmere 100 film, which was willed through the camera, more so than wound.

All photos are untitled because they are simply unworthy of being dignified. They are, essentially, all test shots. And, as such, many aren’t even really “my” test shots, but a collaboration between myself and a malfunctioning camera. None of the photos are as intended. They are, instead, what transpired.

REMINDER: If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.